Read a Short Extract

Chapter 1

Texas 1981

The boat is smaller than he imagined. And dingier.

Even at night Jay can tell it needs a paint job.

This is not at all what they discussed. The guy on the phone said “moonlight cruise.” City lights and all that. Jay had pictured something quaint, something with a little romance, like the riverboats on the Pontchartrain in New Orleans, only smaller. But this thing looks like a doctored-up fishing boat, at best. It is flat and wide and ugly - a barge, badly overdressed, like a big girl invited to her first and probably last school dance. There are Christmas lights draped over every corner of the thing and strung in a line framing the cabin door. They’re blinking erratically, somewhat desperately, winking at Jay, promising a good time, wanting him to come on in. Jay stays right where he is, staring at the boat’s cabin: four leaning walls covered with a cheap carport material. The whole thing looks like it was slapped together as an afterthought, a sloppy attempt at decorum, like a hat resting precariously on a drunk’s head.

Jay turns and looks at his wife, who hasn’t exactly gotten out of the car yet. The door is open and her feet are on the ground, but Bernie is still sitting in the passenger seat, peeking at her husband though the crack between the door and the Skylark’s rusting frame. She peers at her shoes, a pair of navy blue Dr. Scholl’s, a small luxury she allowed herself somewhere near the end of her sixth month. She looks up from her sandals to the boat teeter-tottering on the water. She is making quick assessments, he knows, weighing her physical condition against the boat’s. She glances at her husband again, waiting for an explanation.

Jay looks out across the bayou before him It is little more than a narrow, muddy strip of water flowing some thirty feet below street level; it snakes through the underbelly of the city, starting to the west and going through downtown, all the way out to the Ship Channel and the Port of Houston, where it eventually spills out into the Gulf of Mexico. There’s been talk for years about the “Bayou City” needing a river walk of its own, like the one in San Antonio, but bigger, of course, and therefore better. Countless developers have pitched all kinds of plans for restaurants and shops to line Buffalo Bayou. The city’s planning and development department even went so far as to pave a walkway along the part of the bayou that runs through Memorial Park. The paved walkway is as far as the river-walk plan ever went, and the walk-way ends abruptly here at Allen’s Landing, at the northwest corner of downtown, where Jay is standing now. At night, the area is nearly deserted. There’s civilization to the south. Concerts at the Johnson and Lindy Cole Arts Centre, restaurants and bars open near Jones Hall and the Alley Theatre. But the view from Allen’s Landing is grim. There are thick, unkempt weeds choked up on the banks of the water, crawling up the cement pilings that hold Main Street overhead, and save from a dim yellow bulb at the foot of a small wooden pier, Allen’s Landing is complete blackness.

Jay stands beneath his city, starting at the raggedy boat, feeling a knot tighten in his throat, a familiar cinch at the neck, a feeling of always coming up short where his wife is concerned. He feels a sharp stab of anger. The guy on the phone lied to him. The guy on the phone is a liar. It feels good to outsource it, to put it on somebody else. When the truth is, there are thirty-five-open case files on his desk, at least ten or twelve with court time pending; there wasn’t time to plan anything else for Bernie’s birthday, and more important, there hasn’t been any money, not for months. He’s waiting on a couple of slip-and-falls to pay big, but until then there’s nothing coming in. When one of his clients, a guy who owes him money for some small-time probate work, said he had a brother or an uncle or somebody who runs boat tours up and down the bayou, Jay jumped at the chance. He got the whole thing comped. Just like the dinette set he and Bernie eat off of every night. Just like his wife’s car, which has been on cement blocks in Petey’s Garage since April. Jay shakes his head in disgust. Here he is, a workingman with a degree, two, in fact, and, still he’s taking handouts, living secondhand. He feels the anger again, and beneath it, its ugly cousin, shame.

He tucks the feelings away.

Anger, he knows, is a young man’s game, something he long ago outgrew.

There’s a man standing on the boat, near the head. He’s thin and nearing seventy and wearing and ill-fitting pair of Wranglers. There are tight gray curls poking out of his nylon baseball cap, the words, BROTHERHOOD OF LONGSHOREMEN, LOCAL 116, smudged with dirt and grease. He’s sucking on the end of a brown cigarette. The old man nods in Jay’s direction, tipping the bill of his cap.

Jay reaches for his wife’s hand

“I am not getting on that thing.” She tries to fold her arms across her chest to make the point, but her growing belly is not where it used to be or even where it was last week. Her arms barely reach across the front of her body.

“Come on,” he says. “You got the man waiting now.”

“I ain’t thinking about that man.”

Jay tugs on her hand, feels her give just the tiniest bit. “Come on.”

Bernie makes a whistling sound through her teeth, barely audible, which Jay hears and recognizes at once, It’s meant to signal her thinning patience. Still, she takes his hand, scooting to the edge of her seat, letting Jay help her out of the car. Once she’s up and on her feet, he reaches into the backseat, pulling out a shoe box full of cassette tapes and eight tracks and tucking it under his arm. Bernie is watching everything, studying his every move. Jay takes her arm, leading her to the edge of the small pier. It sags and creaks beneath their weight, Bernie carrying an extra thirty pounds on her tiny frame these days. The old man in the baseball cap puts one cowboy boot on a rotted plank of wood that bridges the barge to the river and flicks his cigarette over the side of the boat. Jay watches it fall into the water, which is black, like oil. It’s impossible to tell how deep the bayou is, how far to the bottom. Jay squeezes his wife’s hand, reluctant to turn her over to the old man, who is reaching a hand over the side of the boat, waiting for Bernie to take her first step. “You Jimmy?” Jay asks him.

“Naw, Jimmy ain’t coming.”

“Who are you?”

“Jimmy’s cousin.”

Jay nods, as if here were expecting this all along, as if being Jimmy’s cousin is an acceptable credential for a boat’s captain, all the identification a person would ever need. He doesn’t want Bernie to see his concern. He doesn’t want her to march back to the car. The old man takes Bernie’s hand and gently guides her into the boat’s deck, leading her and Jay to the cabin door. He keeps close by Bernie’s side, making sure she doesn’t trip or miss a step, and Jay feels a sudden, unexpected softness for Jimmy’s cousin. He nods at the old man’s cap, making small talk. “You union?” he asks. The old man shoots a quick glance in Jay’s direction, taking in his clean shave, the pressed clothes and dress shoes, and the smooth hands, nary a scratch on them. “What you know about it?”

There’s a lot Jay knows, more than his clothes explain. But the question, here and now, is not worth his time. He concentrates on the floor in front of him, sidestepping a dirty puddle of water pooling under an AC unit stuck in the cabin’s window, thinking how easy it would be for someone to slip and fall. He follows a step or two behind his wife, watching as she pauses at the entrance to the cabin. It’s black on the other side, and she waits for Jay to go in first.

He takes the lead, stepping over the threshold.

He can smell Evelyn’s perfume, still lingering in the room - a smoky, woodsy scent, like sandalwood, like the soap Bernie used to bathe with before she got pregnant and grew intolerable of it and a host of other smells, like gasoline and scrambled eggs. The scent lets him know that Evelyn was here, that she followed his careful instructions. He feels a warmth rush of relief and reaches for his wife’s hand, pulling Bernie along. She doesn’t like the dark, he knows; she doesn’t like not being in on something. “What is this?” she whispers.

Jay takes another step, feeling along the wall for the switch.

When the light finally comes, Bernie lets out a gasp, clutching her chest

Inside the cabin there are balloons instead of flowers, hot links and brisket instead of filet, and a cooler of beer and grape Shasta instead of wine. It’s not much, Jay knows, nothing fancy, but, still it has a certain charm. He feels a wave of gratitude - for his wife, for this night out, even for his sister-in-law. He had been loath to ask for Evelyn’s help. Other than his wife, no one seems more acutely aware of Jay’s limits than Evelyn Annemarie Boykins. She’s been on him for two weeks now, wanting to know was Jay gon’ get her baby sister something better for her birthday than a robe he bought Bernie last year, what cost him almost $30 at Foley’s Department Store. He couldn’t have done tonight on his own, not without his wife suspecting something. So he was more that grateful when Evelyn offered to pick up some barbecue on Scott Street and blow up balloons. Everything will be ready, she said. In the centre of the room is a table set for two, a chocolate cake, with white and yellow roses, just like Evelyn promised. Bernie stares at the cake, the balloons, all of it, a slow smile spreading across her face. She turns to her husband, reaching on her tiptoes for Jay’s neck. Pressing her cheek to his. She bites his ear, a small, sweet reprimand, a reminder that she doesn’t like secrets. Still, she whispers her approval. “It’s nice, Jay.”

The boat’s engine starts up, Jay feels the pull of it in his knees.

They start to slow coast to the east and out of downtown, beads of water rocking and rolling across the top of the air-conditioning unit. The moist, weak stream of air it offers isn’t enough to cool an outhouse. The room is only a few degrees below miserably hot. Jay is already sweating through his dress shirt. Bernie leans against the table, fanning herself, asking for a pop from the cooler.

There’s a Styrofoam ice chest resting in one corner. Jay bends over and pulls out a soda can for his wife and a cold beer for himself. He flicks ice chips off the aluminium lids and wipes at them with the corner of his suit jacket, which he then peels off and drapes on the back on his chair. Next to the cooler is a stereo set up on a card table, black wires and extension cords dripping down the back and onto the floor. Jay kicks the wires out of view, thinking of someone tripping, a slip or a fall. Bernie soon takes full charge of the music, fishing through Jay’s shoe box, passing over her husband’s music - Sam Cooke and Otis, Wilson Pickett and Bobby Womack - looking for some of her own. She’s into Kool & the Gang these days. Cameo and the Gap Band. Rick James and Teena Marie. She slides in a tape by the Commodores, which at least Jay can stand. Just to be close to you… the words float across the room. Jay watches his wife, swaying to the music, dancing, big as she is, the tails of her two French braids swinging in time. He smiles to himself, thinking he’s got everything he needs right here. His family. Bernie and the baby. All he has.

There’s a sister somewhere.

A mother he isn’t talking to.

Old friends he’s been avoiding for more than ten years. He hasn’t spoken to his buddies - his comrades, cats from way, way back-since this trial. The one that nearly killed him. The one that drove him to law school in the first place. He started missing meetings, after that, skipping funerals, ignoring phone calls, until, eventually, his friends just stopped calling. Until they got the hint.

He counts himself lucky, really.

A lot of his old friends are dead or locked up or in hiding, out of the country somewhere; they are men who cannot come home. But Jay’s life was spared. By an inch, a single juror: a woman and the only black on the panel. He remembers how she smiled his way every morning of the trial, always with a small nod. It’s okay, the smile said. I got you, son. I’m not gon’ let you fall.

After the trial, after he’d checked himself in and out of St. Joseph’s Hospital, he learned the juror, his angel, was a widow who stayed out on Noble Street, down from Bernie’s Church, the same church where her father, Revered Boykins, had loaded a bus with half his congregation every morning of Jay’s trial. They were women mostly, dressed in the best stockings and felt hats and cat eye glasses with white rhinestones. They rode to the courthouse every day for two weeks simply because they’d heard a young man was in trouble. No questions asked, they’d claimed him as one of their own. They sat through days of FBI testimony, including a secret government tape that was played in the hushed courtroom - a tape of a hasty phone call Jay had made in the spring of 1970.

The prosecutors had him on a charge of inciting a riot and conspiracy to commit murder of an agent of the federal government - a kid like him and a paid informant. They had Jay on tape talking to Stokely, a phone call that ran less than three and a half minutes and sealed his fate. Jay, nineteen at the time, sat at the defense table in a borrowed suit, scared out of his mind. His lawyer, appointed by the judge, was a white kid not that much older than Jay. He wouldn’t listen and rarely looked at Jay. Instead, he slid a yellow legal pad and a number 2 pencil across the table. Anything Jay had to say, he should write it down.

He remembers staring at the pencil, thinking of his exams, of all things.

He was a senior in college then and failing Spanish. He sat at the defense table and wondered how old he would be when he got out, if they gave him two years or twenty. He tried to imagine the whole of his life - every Christmas, every kiss, every breath - spent in prison. He tried to do the math, dividing his life in half, then fourths, then split again, over and over until it was something small enough to fit inside a six-by-eight cell at the Walls in Huntsville. Any way he looked at it, a conviction was a death sentence.

He remembers looking around the courtroom every morning and not recognizing a soul. His friends all stayed away, treating his arrest and pending incarceration as something contagious. He was humbled, almost sickened with shame to see the women from the church, women he did not even know, show up every day, taking up the first two and three rows in the gallery. Never speaking, or making a scene. Just there, every time he turned around.

We got you, son. We’re not gon’ let you fall.

His own mother hadn’t come to the courthouse once, hadn’t even come to see him in lockup.

He didn’t know Bernie then or her father, didn’t know the church or God. He was a young man full of ideas that were simple, black and white. He liked to talk big about the coming revolution, about the church negro who was all show and no action, who was doing nothing for the cause… a word spoken one too many times, worked into one too many speeches, until it has lost all meaning for Jay, until it was just a word, a shortcut, a litmus test for picking sides.

Well he’s not on anyone’s side anymore. Except his own.

There are other American dreams, he reasons.

One is money, of course. A different kind of freedom and seemingly within his reach. If he works hard, wears a suit, plays by the new rules.

His dreams are simple now. Home, his wife, his baby.

He watches Bernadine, moving to the music, wiping sweat from her brow, pasting stray black hairs against her bronze skin. Jay stands perfectly still, lost in the sway of his wife’s hips. Right, then left, then right again. He smiles and leans over the cooler for a second beer, feeling the boat moving beneath his feet.

An hour of so later, the cake cut and the food nearly gone. Jay and Bernie are alone on the deck, trading the hot, humid air inside the cabin for the hot, humid air outside. At least on the deck, there’s the hope of a breeze as the boat travels west on the water. Bernie leans her forearms against the hand railing, sticking her face into the moist night air. Jay pops the top of his Coors. His fourth, or maybe his fifth. He lost count somewhere near Turning Basin, the only spot between downtown and the Port of Houston where a boat can turn around on the narrow bayou. They are heading back to Allen’s Landing now, but are still a few miles from downtown. From the rear of the boat, Jay can see the lights of the high-rise buildings up ahead, the headquarters of Cole Oil Industries standing tall about the rest. To the rear of the boat is a view of the port and the Ship Channel, lined with oil refineries on either side. From here, the refineries are mere clusters of blinking lights and puffs of smoke, white against the swollen charcoal sky, rising on the dewy horizon like cities on a distant planet.

Between the refineries and downtown Houston, there’s not much to look at but water and trees as the boat floats through a stretch of nearly pitch-black darkness. Jay stands next to his wife on deck, following shadows with his eyes, tracing the silhouette of moss hanging from the aged water oaks that line the banks of the water. He finishes his beer, dropping the can onto the deck.

They are about to head back inside when they hear the first scream, what sounds at first like a cat’s cry, shrill and desperate. It’s coming from the north side of the bayou, high above them, from somewhere in the thick of trees and weeds lining the bank. At first Jay thinks of an animal caught in the brush. But then…. he hears it again. He looks at his wife. She too is staring through the trees. The old man in the baseball cap suddenly emerges from the captain’s cabin, a narrow slip of a room at the head of the boat, housing the gears and controls. “What the hell was that?” he asks, looking at Jay and Bernie.

Jay shakes his head even though he already knows. Somewhere deep down, he knows. It wasn’t an animal he heard. It was a woman.

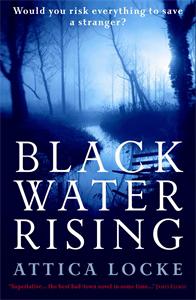

Reproduced by permission of Serpents Tail

Copyright © 2009 Attica Locke